There's Always Hope

We are continuing to celebrate our 25th Anniversary throughout 2014, and as part of that, we are reprinting old articles that convey chapters in our history. Tim Dunn was a volunteer and staff person in our early years, starting at our very first shelter in the winter of 1989. He wrote this article as part of HOME at Ten, a collection of prose, poetry, and artwork published in 1999 as part of our tenth anniversary celebration.

We are continuing to celebrate our 25th Anniversary throughout 2014, and as part of that, we are reprinting old articles that convey chapters in our history. Tim Dunn was a volunteer and staff person in our early years, starting at our very first shelter in the winter of 1989. He wrote this article as part of HOME at Ten, a collection of prose, poetry, and artwork published in 1999 as part of our tenth anniversary celebration.

Ten winters ago I worked in Project HOME’s very first program. It was the Mother Katharine Drexel residence located in the locker rooms of the Marian Anderson Recreation Center in South Philly. I didn’t have much hope for Project HOME becoming much of anything. Our beginning didn’t seem very promising to me. The staff was a skeleton crew, each of us worked three fourteen-hour shifts a week. I had worked the previous two winters in a couple of shelters, and I thought I knew something. That first winter with Project HOME I learned how little I knew.

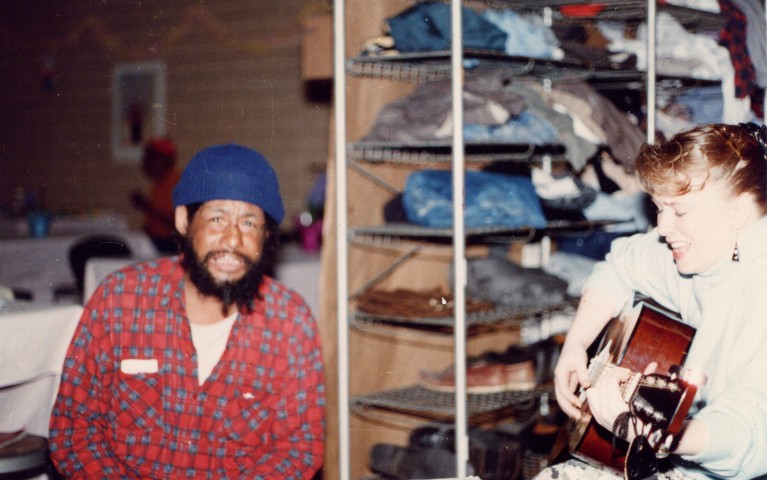

The locker rooms at the Rec Center became home for some of the Center City’s most vulnerable homeless men. Most of these men were mentally ill or addicted; some dressed in rags; some had burn marks from sleeping on steam vents. Some of them were thieves; some were abusive and potentially violent. Many of these men were difficult and demanding, but I learned a lot from them. I learned their struggles and strengths, their beauty, their capacity to change.

Some of them have passed, but I was witness to their homecoming, to their character, to their dignity. Men like Preston Owens, Horace Green, Jeffrey Two Feathers, and Marion Christmas gave birth to the spirit of Project HOME. I also learned from the men and women of that skeleton crew I worked with, particularly Joan Dawson McConnon, whose compassion for these men was boundless.

But it was another person that first Project HOME winter who taught me the largest lesson, one that took me a few years to learn. Those mornings after my long shifts overnight at that crazy shelter at the Rec Center, I’d always ride my bike past the same homeless guy. This guy was always out there, rain or shine, crouched on the sidewalk in West Philly. To me he looked like a caveman dressed in rags. Most mornings I saw him he was carrying on a very heated conversation with no one apparent. Some mornings I’d see him scream and point, his matted hair gave the impression of some wild animal. When I saw this guy, I’d say to myself, “How the hell could they ever get someone like this guy off the street?”

Although I saw little hope for this man, we crossed paths later in my life. I must confess here that I was wrong about Project HOME. Our humble beginning on the locker room set the stage for our steady growth and expansion, but most importantly for our commitment to homeless people in Philadelphia. Around Project HOME’s fourth year I became a staff person at a new Project HOME site, a place called Kairos House, a residence for homeless men and women suffering from mental illness.

One of the staff showed me around and introduced me to the residents. It was a lovely place, so far from those locker rooms. Nice carpeting, private rooms. The residents seemed happy, too, especially the guy who like jazz. He seemed oddly familiar to me. Then I realized that he was the very same guy I used to see on the sidewalk in West Philly that first Project HOME winter.

A question here: Which is worse, to be “hopeless” or to be “lacking in hope?” This man taught me the largest lesson, that there’s always hope. Kairos House was a homecoming for both of us: “home” for him, “hope” for me.